A Cruise Up the Elbe: October 2012

A number of friends, having seen TV advertisements for Viking River Cruises, have asked us for a report on our Elbe cruise. We were surprised to discover how big a company it is — originally Scandinavian and Dutch owned, now Los Angeles based, we gathered, and expanding rapidly. They sail a number of newly built ‘Longships’ and more are commissioned. Viking may now be the biggest river cruise operation and it seems they have done this largely by extensive and carefully researched product placement and TV advertising — especially in the United States, where they sponsor Downton Abbey (which is madly popular on Public Broadcasting Service). Our ship, the Theodore Fontane, had its full complement of 110 passengers and I remember only 16 as British. There were perhaps three Canadian couples, but like many Canadians they were so unobtrusive as to be virtually invisible; and there was one Australian couple. The rest were US-Americans of varying degrees of eccentricity.

There are two Viking ships running the Elbe cruise back and forth between Berlin and Prague: you can either go to Prague and sail to Berlin or vice versa. Because we wanted to spend an extra night in Prague, we chose to start in Berlin so that at the other end we would acquire some familiarity with Prague before we were left to our own devices when the rest of our party flew off home. We were ‘warned’ that they usually booked their American passengers on the Berlin-to-Prague leg, and their UK passengers in the other direction, but we assured them that we didn’t object at all to sharing our ship with Americans. We realised that there were reasons for their policies. A high proportion of the Americans are frequent cruisers with Viking, and some of them told us that one of the reasons, apart from Downton, is the very favourable discounted airfares which Viking manages to provide. I suppose bulk booking helps with that. Also a number of them tend to do consecutive cruises while they are in Europe, so for example they can do Berlin-Prague and then from Prague they can transfer to a Viking river cruise through Budapest and Vienna to Amsterdam, or Prague to Paris. Some of them were on their sixth Viking cruise. Perhaps UK passengers are less likely to do multiple cruises.

Viking lives up to its glossy advertisements as far as organisation goes. All the travel arrangements were meticulous — a great contrast with our only previous river cruise with another cruise firm on the Portuguese River Douro, where we arrived at Porto airport on a winter’s night and the tour representative had apparently gone AWOL. This time we were met and marshalled at Berlin as we came through customs and from then on were beautifully looked after. The first of many luxury coaches with an excellently informative guide drove us into a splendidly situated Berlin Hilton. We were issued with our room cards as we left the coach, and our luggage followed us to our rooms — no check-in nonsense. Getting as far as Berlin had been enough travelling for one day so we didn’t join the walking tour to the Brandenburg Gate. But we did walk just a few hundred yards to one of the three restaurants of varying prices within walking distance of the Hilton recommended by our Viking minder — and very good and genuine it was too. This was Lutter & Wegner, opened in 1811, a survivor of European wars and 40 years of DDR government. (There’s a possible problem with that hyperlink: if clicking it doesn’t open it, just copy http://www.unlike.net/berlin/food/lutter-and-wegner/ into your browser.)

It was a return to Berlin for us. We had got to know parts of it quite well during our years in Warsaw in cold war days. Berlin was for us a lifeline for some basic services, as Helsinki was for the British Embassy in Moscow. On visits to Berlin for essential shopping or for medical treatment we used to stay in the NAAFI Hotel/Hostel, along with British military personnel and their families in transit, and shopped at the NAAFI which also supplied our Embassy shop in Warsaw. We crossed into the US zone to shop at the PX and enjoyed the French equivalent in the French zone. We shopped and marvelled at the famous KaDeWe, West Berlin’s rival to Harrods and visible flagship of its flamboyant prosperity in contrast to the drab scenes over the Wall. I had also marvelled at the size of West Berlin and its vast expanses of forests and lakes: when the Berlin airlift was operating 24 hours a day between June 1948 and May 1949 to keep the city and its inhabitants alive, I had always envisaged it as a large overcrowded council estate! In 1985 we had driven to and from Warsaw for home leave. This involved driving through East Germany, the GDR, on an approved route, our car monitored as in the Soviet Union by successive checkpoints, and then driving round the edge of Berlin until we reached the correct crossing point into West Berlin (we were banned from driving through East Berlin, for some obscure doctrinal reason, unless armed with permits to stay there). We stayed with FCO friends who were serving in the British Military Government. The BMG, with the US and French, still had de jure responsibility for governing Berlin. From them we learned the important arcane Cold War protocols which governed crossings into East Berlin, giving rise to many espionage and other dramas.

Before we left Warsaw we stayed in East Berlin with the British Ambassador to the GDR and were able to compare the drab attempts of the East German régime to compete with the glossy scenes on the other side of the Wall. But the East had the museum island. Some of the buildings had been reconstructed and reopened by the 1980s, other have been restored since reunification in 1990. And in East Berlin they had the Unter den Linden with its iconic memories and buildings.

Although at the start of our river cruise we only stayed overnight in Berlin it was a time of pungent memories and poignant thoughts. Crossing a line of two cobblestones in the roadway marking the line of the Wall as we drove from the airport to our hotel signified the historic end of so much that had dominated both our childhood and our adult years.

The Elbe trip started in earnest the next morning when we embarked back on the coaches and drove to Potsdam, stopping on the way for a photograph opportunity at the Gliecke Bridge, scene of four cold war spy or prisoner swaps.

In Potsdam we toured the Sans Souci palace, found ourselves lunch in the Dutch quarter and then saw — from the outside only — the Cecilienhof Palace where the Potsdam conference was held in July and August 1945 — Attlee, having won the 1945 election and succeeded Churchill as prime minister, replacing Churchill for the latter part of the conference. The Cecilienhof is one of the many Hohenzollern family palaces in Potsdam and was completed only in 1916 while the Battle of the Somme was raging. It was built for Kaiser Bill’s heir and his wife, Crown Princess Cecilie, in English Tudor style. The Crown Princess apparently lived on in the Palace until February 1945 when the Soviet forces arrived. (I still don’t understand the causes of the Great War, as it was still called in my childhood.)

From Potsdam we drove on to Magdeburg where Theodore Fontane was moored and waiting for us. Magdeburg had been an RAF target in the campaign to destroy German oil production and, according to Wikipedia, much of the city was destroyed on the night of 16 January 1944. Our guide pointed out the towers of the rebuilt cathedral as we passed through and mentioned the bombing and destruction in a neutral way, as did most of our guides throughout our tour. Only after our visit to Dresden did something trigger words between some British passengers towards the front of the coach and the guide. No blows were exchanged.

It was good to board the ship but I don’t think the Fontane features in the Downton Abbey advertisements. She and the other Viking ship which ply the Elbe are the smallest and oldest of the Viking fleet: they need to be because the Elbe is quite shallow in places and one of the locks we went through was alarmingly narrow. In a mainly chilly October the 110 passengers were rarely able to take advantage of the spacious and comfortable sun deck and without this the Fontane lounge often felt crowded. But the food was good, the house wine (included) was very drinkable and flowed generously, and everything worked like clockwork. If ever we wanted to do a river cruise again we would choose Viking — but on a bigger ship.

It was good to board the ship but I don’t think the Fontane features in the Downton Abbey advertisements. She and the other Viking ship which ply the Elbe are the smallest and oldest of the Viking fleet: they need to be because the Elbe is quite shallow in places and one of the locks we went through was alarmingly narrow. In a mainly chilly October the 110 passengers were rarely able to take advantage of the spacious and comfortable sun deck and without this the Fontane lounge often felt crowded. But the food was good, the house wine (included) was very drinkable and flowed generously, and everything worked like clockwork. If ever we wanted to do a river cruise again we would choose Viking — but on a bigger ship.

Once we left Magdeberg, we found ourselves constantly reminded of Russia and Soviet times as we sailed past the somewhat unkempt East German countryside. We saved our energies for the main stopping points, Wittenberg, Meissen, Dresden and Prague, and opted out of excursions in other small towns where we docked. In these we just pottered around at our own pace and noted the effects of the forty years of GDR neglect which had followed the depredations of total war. Potentially picturesque streets of houses and shops, with peeling paint and pock-marked walls, seemingly holding each other up, have yet to benefit from the largesse of reunification: shop windows, while almost certainly displaying a wider choice than would have been available in Erich Honecker’s time, still had that fly-blown style of Soviet retail displays.

Wittenberg, Martin Luther’s home, was the first excursion we joined and we were glad we did. The ebullient cruise director, in his maiden season with Viking after thirty year as an entertainer on ocean cruises, seemed to go down well with the American despite, or because of, his constant declarations that he was a cockney and proud of it. He said, a trifle mysteriously, that he assumed that only the Americans would be interested in the Martin Luther connection. For the benefit of the British he told us about the shopping opportunities in Wittenberg including the fact that Wittenberg for some reason is home to a branch of C&A. (We didn’t see anyone peeling off for that.) We felt we had a connection with Wittenberg because of Brian’s German Lutheran ancestry. His many times great-grandfather, Lutheran Pastor Christopher Frederick Triebner, was a graduate of the nearby Lutheran university of Halle and he would have known the cities of the Elbe before he was posted in 1767 to minister to German Lutherans in the newly founded British American Colony of Georgia. There was no mention of Wittenberg being bombed or otherwise unduly affected during the war, and the Honecker regime seems to have neglected rather than destroyed the buildings with Martin Luther connections. The Castle Church where Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses, setting out a ‘devastating critique of the church’s sale of indulgences’, was badly damaged by the French in 1760 during the Seven Years War, but it has survived ever since. Other buildings, including the Black Monastery (Augustinian) where Luther lived as a monk, and which later became his family home, have been rescued from neglect, as have buildings associated with the Cranach family of painters. Wittenberg seems to be modestly flourishing as a tourist destination on the coat-tails of Martin Luther. It was strangely fascinating to learn more of this extraordinary man, with his questioning mind and refusal to acquiesce in intellectual chicanery or corruption. Why, Brian wondered, didn’t he go all the way?

Another excursion we did opt into was a night-time walking tour of Torgau where US and Soviet (Ukrainian) troops met up on 25 April 1945, Elbe Day: as Wikipedia relates, US troops later withdrew under the terms of the Yalta agreement.

We docked at Torgau during dinner and were due to leave again at dawn the next morning. At 9pm three intrepid Viking staff with torches led us elderly passengers , some leaning on their sticks, through the pitch-dark winding cobbled streets of Torgau. There were no street lights and no lights in houses — London in the blackout syndrome. Eventually we arrived at the handsome main square with its memorial to the historic meeting and a fine fountain. The square has been restored since reunification and was illuminated largely by the lights of a large cafe with inviting tables and chairs outside. It could have been any European city square. But there was no sign of customers, inside or out, and throughout our walk we saw only one car and one man walking a dog. Our congenitally exuberant cruise director, whose up-beat unflagging enthusiasm was a tonic thoughout the cruise, had told us, with ribald speculation, that in all his evening visits to Torgau he had never seen any sign of people. The Viking handler of our group, a Pole named Patrick, in an impassioned and presumably unscripted outburst, told us that the reason there were no people on view was because they were all too poor to be out enjoying themselves. According to him, unemployment is very high, Villeroy Boch is the only employer, and wages are low. Patrick’s nationality background is of the kind that makes loyalties within Europe impossible for British people to fathom. He comes from Szczecin (previously Stettin), once Slav, then Swedish, and from 1720 firmly Prussian. In the post-war settlement Russia shifted its borders westwards by absorbing large swathes of eastern Polish territory and the Poles were compensated with Prussian territories to which they had always laid claim as part of the once huge Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, once stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and Stettin became Polish as Szczecin. Winston Churchill was still calling it Stettin in the Fulton speech of March 1946 when he said, famously: “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.” German inhabitants of Stettin were part of that largely unrecorded, massive ethnic cleansing which accompanied the shifting of Polish frontiers. Thousands of Germans were expelled from the new Poland and thousands of them perished in the process. Patrick’s Polish grandparents were moved into Stettin, and the original German owners of the house which was allocated to them not only survived but managed to make contact with the new occupants. The families, both originally casualties of the war, have kept in touch and they have even inter-married. We often used to hear stories like this in Gdansk.

We also braved the excursion in Meissen — which was probably a mistake, because it condemned us to an interminable visit to the Meissen porcelain factory and museum. We should have learned from past multiple tedious experiences: we don’t enjoy seeing porcelain being made or painted, however skilful the workers-artists-craftspersons, and we had no intention of buying a piece to take home, even if any of it had not been grossly over-priced. So we eventually took refuge from the tour in the museum’s coffee-shop. Once released from that we made our own way back to the ship through the old market square and realised that we could and should have walked in to the town by ourselves, and skipped the porcelain.

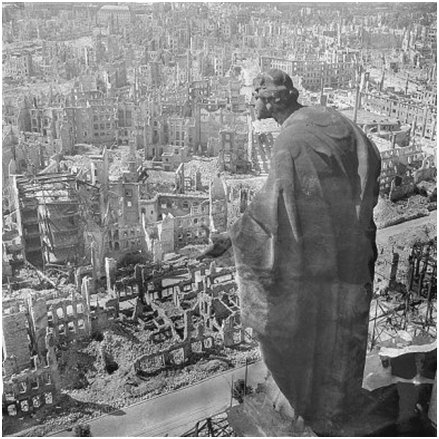

On the other hand we are very glad that we braved (in all senses) the Dresden excursion. Once again we had a splendid guide. I was relieved to find that Dresden was a big enough city to mean that at least some areas escaped the wrath of RAF bombs on the night of 13/14 February 1945 with a follow-up from US bombers, and the colossal firestorm which they set off. In the Neustadt area there are many late nineteenth century baroque and art nouveau buildings now being renovated as homes for the rich as well as providing café and artistic quarters. But, as we know, the inner city, a mixture of residential and priceless historical and ecclesiastical buildings, was completely destroyed by the tons of bombs which fell in one night, and the consequent firestorm, fanned by the gales it generated and spread by the vacuums where the oxygen was sucked into the blaze . Controversy still rages over the reasons for a raid of such savagery so late in the war, causing so many casualties, and whether or not the firestorm effect was predicted and planned or genuinely accidental. It takes more than Wikipedia to provide answers.

We know that thousands died and we also know that many of them were already refugees, famously a huge number fleeing the approaching Soviet Armies. We also know that many internationally cherished buildings were reduced to smoking embers. Many of these, including the Semper Opera house and the Zwinger Palace, were lovingly restored by the East German regime and, as in Warsaw, we could see them as tourists without necessarily realising that they were restorations. But the East Germans had left some areas completely untouched and it was only after reunification that work began on restoration. The upside of this is that treasures such as Frauenkirche, The Church of Our Lady, once symbol of Dresden, were not demolished as other damaged buildings were. It was finally restored in 2005 and topped with a gold cross donated by the city of Edinburgh and designed by the son of one of the RAF pilots on the bombing raid.

Dresden, 1945, view from the city hall (Rathaus) over the ruined city (the allegory of goodness in the foreground).

We rested from our excursion exertions as the ship sailed through the area known as Saxon Switzerland, with its spectacular gorges and dramatic sandstone cliffs, presumably the area which provided material for so many of Dresden’s sandstone buildings. While the rest of the crowd went off on the usual convoy of three coaches, we pottered round the small Spa town of Bad Schandau. Eighteenth and nineteenth century buildings in the main square showed the usual signs of years of neglect. But a large modern expensive spa hotel perhaps presaged signs of revival. And finally, steaming again silently through the night along the Elbe, we crossed into the Czech Republic. Brian noticed that the Elbe immediately looked polluted with foamy detergent floating along beside us, unlike the condition of the river in Germany – even east Germany. Once we got to Prague, we were interested to hear our guide routinely refer to the country as ‘Czech’, without the ‘Republic’. It still sounds bare without Slovakia.

Our first stop in ‘Czech’ was Litomerice, in Bohemia (or Sudetenland, word that still resonates). Once again we chose to guide ourselves, despite thereby missing out on a visit to a brewery. (This was probably just as well. We were told by those who went that instead of the tasters they were expecting they were plied with a succession of full tankards and found it difficult to concentrate for the rest of their guided tour round the town.) The main square has a number of substantial attractive buildings, civic and ecclesiastical, and there are signs of restoration and renovation. But it had gone to sleep. It was a Saturday and the shops had closed at 11.30am. Our American companions complained loudly when they got back on board. If they were running a shop in a poor town where a boat full of foreign tourists called twice a week they would make sure to be open whenever the boat arrived. We joined the Czechs drinking coffee in a café on the square and didn’t regret the shops being closed. They didn’t seem to have anything we wanted anyway. We read afterwards that most of the German population of the town was expelled in August 1945 along with about two million other ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia. In fact the town had been mainly German anyway since the defeat of the Protestants under the Winter Queen, Stuart-born Elizabeth of Bohemia, and her husband Frederick V at the beginning of the Thirty Years war. Czech Protestants left, German Catholics remained, and Litomerice became a Catholic bishopric.

During the following night, we reached a point on the river as near to Prague as the Elbe could take us and, after breakfast, we transferred to our coaches for the 45-minute drive to the Prague Hilton Hotel. Historic Prague covers a large area and (unlike almost any city in Poland, for example) seems to have escaped the second world war virtually unscathed. Street after street in the old town look like newly painted stage sets. There are crowds of tourists in groups and some streets on the outskirts of the old town obviously cater for the tourist with money – shops seemingly transported from the smart shopping areas of Milan or Florence. We tried in vain, over a day and a half, to get a table at the fabulous Imperial Hotel restaurant. Obviously we should have booked before we left. We looked at it and it was fantastic. But we ate at another restaurant just by the Charles Bridge, nothing like the Art Deco Imperial, but seemingly unchanged from the days when prosperous Czechs might have dined there in Austro-Hungarian days. The little we saw of Prague outside the heritage areas looked much more Soviet, with depressing badly maintained buildings. But they seemed to have a very good and modern tram and subway system which we credited to Communist planning. Our guide told us that many Czechs had collaborated with the Nazis, though we remembered the assassination of the Nazi war criminal Heydrich by Czechs at the behest of the British in 1942, and the brutal reprisals that followed. And we remember the Czechs who, like the Poles, played a crucial role by their brave, even foolhardy flying, in the Battle of Britain. The guide also observed that after the war the Russians didn’t need to occupy Czechoslovakia because the home-grown communists did everything that was expected of them. But there was a Russian occupation from after the Czech spring of 1968 until 1990 and she was one of those who had taken part in the 1989 protests that brought about the Velvet Revolution and the withdrawal of the Russian army of occupation. Ethnicity, family experience and age must colour interpretations of the tragedies that have overwhelmed Europe through the centuries.

After a comfortable night at the Prague Hilton and a lavish breakfast the next morning, our Viking experience had ended. But we stayed on for an extra day of sight-seeing and to recover before facing the unwelcome prospect of airports, security checks and Heathrow holding patterns.

It was a good time and we have come back with many resolutions to follow up on things we realise we don’t know. I have ordered two accounts of the Dresden bombing from our local public library as a start (and probably as a finish). We may, though, occasionally refresh our memories of the cruise by once more clicking through our web album of photographs.

JB

London, October 2012